***SPOILER ALERT****

I had high expectations of this film, part of a reaction to the nonsensical idiocy that was The Clash of the Titans. I wanted to enjoy an epic that portrayed the ancient world as it was. It hasn’t been a disappointment – I think it’s a must see, simply because of what it portrays. Moreover, the way the film brings Alexandria to life is splendid, though I would have loved to see a scene set in the infamous lighthouse, just for the hell of it.

One thing I will warn others of though is that it is rather a brutal telling of the events surrounding the fall of the Empire and the rise of Christianity within Alexandria, so this isn’t for the faint hearted.

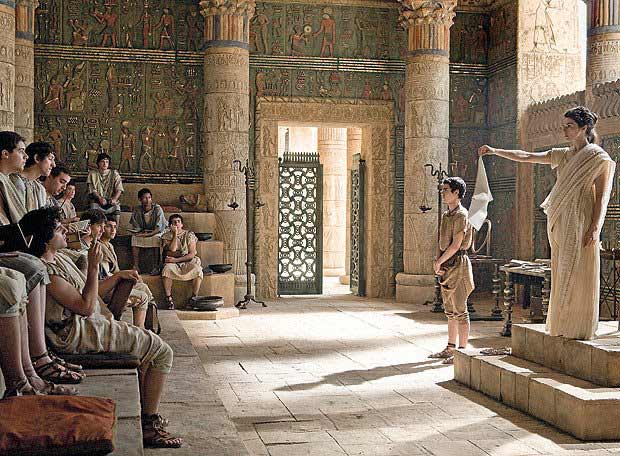

The film follows Hypatia, a philosopher and teacher and it opens with her musing about the force that allows our feet to stay on the ground and brings a cloth floating down; centuries ahead of Isaac Newton we see. She is talking about it with her group of students in the ‘agora’, the Greek word for a place of assembly – think Roman forum. Rachel Weisz is brilliant in the lead role, with a perfect balance of scholarly, wide eyed excitement and heavy eyelids filled with disappointment and veiled horror at what is being allowed to happen in the city. Alongside her story, the story of Alexandria unfolds, where the Christians begin to brazenly mock the previous pagan religions (I despise using the word ‘pagan’, simply because of its connotations; I’d rather use a word that doesn’t denote such disrespect). This incites the followers of the Egyptian religion and so ensues a horrible back and forth which sees the Christian majority driving out the Jews and banning the practice of anything ‘pagan.’ It makes for very uncomfortable viewing. I think I must have had a past life around that era, because the scene where the Christians run into the library – the most famed library in the world at that point, for it held knowledge untold, where Hypatia and her father study - and destroy it and its scrolls, really hit me in the chest. I had to hold back cries of outrage (yes, I know it’s a film but it did happen and the film scores points for being able to pull me in so relentlessly). My heart wept as Hypatia cried over the loss of the library.

Alejandro Amenabar doesn’t hold back on showing the manipulation and madness that surrounds the Christians in their bid to overtake the city. In one scene where the bishop Cyril reads a passage from the Bible where it’s written that women are not be listened to or trusted for advice, you get the distinct impression he is making it up – a brave statement to depict the corruption and persuasion surrounding interpretations of the Bible. Not only that, its obvious the Christians are displayed as carnal, while a veneer of virtue surrounds Hypatia and the sacred space of her studies and theorising. They are the brutal executioners, only ever seen with blood stained swords and she is civilisation, devoted to understanding the cosmos and our magnificent link to the sun. The character of Orestes gives a brilliant line in the film when he remarks how offended the Christians seem to get when creation or the universe is questioned. This summed up a brilliant conflict that the film flags up between philosophical science, (pioneered by the Greeks) and the idea of submission to a God or the word of God, (as delivered by Christians and later, Islam). While ancient religions (and eastern religions to this day) operated by questioning existence, western religions have operated to only encourage compliance.

Hypatia notes to Synesius 'You do not question your beliefs or cannot. I must.'

The ancient Greeks were aware of that their religion and mythology was simply poetry, symbols to associate things with, never to be taken literally. Instead, their time was spent studying the cosmos and the idea of life as humans, often through the metaphor of dramatic poetry. Instead, the literal interpretation of the laws of heaven is where the danger starts and the film brings that to light brilliantly; this same literal interpretation has raped the pursuit of knowledge and resigned people to madness rather than exploration.

Performances delivered by Oliver Isaacs as the Roman prefect torn between politics and the woman he is devoted to is right on the mark, as was Rupert Evans as Synesius and Max Minghella as Davus, Hypatia’s slave turned ‘Christian soldier.’ He barely has any lines but his face says it all and he is last ditch attempt to save the woman he loves is somewhat redeeming but it is too late.

Though set in ancient times, it’s still relevant; killing in the name of God, blind religion destroying exceptional knowledge and progress, the role of woman married to her science rather than a man etc. It’s a wonder that centuries ago, people were able to come to the mind-blowing conclusions about the sun and the planets without so much as papers, pen and sticks, and the modern man has utilised endless amounts of technology to come confirm what was already known (and then lost! - it's always frustrated me how we're made to believe these discoveries were made in 1600s/1700s etc) Alas, that the library was destroyed – goodness knows what gems were stored there! Well, they only did themselves in, as displayed in the dark and violent Christians who foreshadow the coming of the Dark Ages.

Powerful and hard hitting, this film is worth watching, even for its length. 9/10.

No comments:

Post a Comment